When we listen to spoken language, we have to rapidly recognize words as they arrive one after another. This rapid timing of spoken language creates a challenge for listeners, but perhaps an even more difficult problem for scientists studying how listeners recognize words as they hear them. It’s easy to measure what people recognize by the time they are done figuring it out – we can ask them to repeat the word that they heard, or have them choose a picture that matches the word – but this doesn’t tell us how they recognized that word as it was being heard.

For example, think about hearing the word sandal. After we hear this word, it’s easy to think of open-toed shoes that we’d wear to the beach. But as we hear it, how is our brain recognizing this word, and ignoring others? Do we wait until the end of the word, and then try to figure out which word we heard? Or do we start trying to recognize the word right away, and keep updating our guesses as we get more information? Asking listeners what word they heard after the word is over might miss out on important details of how they got there.

Over the past couple decades, cognitive scientists have developed clever solutions to studying what listeners’ brains are doing as they hear words. Among these techniques, eye-tracking has proven one of the most versatile and informative ways to measure how people recognize spoken words. Eye-tracking sounds like a weird way to study spoken language – what can the eyes tell us about how the ears hear words? But through careful experimental design, it turns out that eye movements provide valuable insight into language processing.

We move our eyes constantly to focus on different things in the environment – sometimes making eye movements multiple times per second. These eye movements tend to be done without conscious thought; we naturally move our attention to things that we need to see without having to think about where to move them. This unconscious, rapid use of eye movements makes them a great way to see what people are thinking as they process information. For studying word recognition and spoken language, we can measure where people look as they hear words to see what their mind is considering before they make a decision.

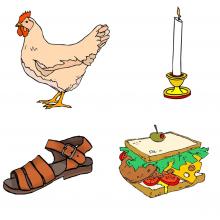

Let’s return to our sandal example. If we ask listeners what word they heard after they hear the whole word, they’ll almost always correctly say sandal, but we will miss all the things that happened before they knew what the word was. If we instead use eye-tracking, we can see what they consider before deciding that they are hearing sandal. For example, we can show listeners a display that includes a sandal, a sandwich, a candle and a chicken. Notice that sandal and sandwich start with the same sound, and sandal and candle rhyme. With eye-tracking, we can measure whether listeners look to both the sandal and the sandwich early in the word, after hearing sand – that is, whether they start making guesses about what word they are hearing before they hear the entire word. Similarly, we can see if they ever look to the candle, even though it doesn’t match the beginning sound of what they heard. We can compare how much they look at these words that have similar sounds to how much they look at the chicken, which sounds nothing like sandal. Tracking these eye movements can tell us how much people consider other, similar-sounding words during word recognition, and exactly when they consider them.

Many past studies show that listeners show just these patterns of eye movements to competing items. Listeners start making eye movements almost immediately after the beginning of a word, and those eye movements are mostly toward items that have the same beginning sounds they are hearing – they look to the sandal and the sandwich. Once they hear enough to tell them which words are incorrect – when they hear the –al part of sandal – they stop looking at the words that don’t match – eye movements to the sandwich stop. But late in words, rhyming words start to be fixated a little bit; listeners will make a few eye movements toward the candle, as it mostly matches what they heard. After all of this activity, they can say they heard the word sandal, but we have gotten a lot more insight into what happened before they got there.

Eye-tracking is a valuable tool to study these processes and others in word recognition and spoken language processing. Growing Words uses several eye-tracking tasks to understand how children recognize both spoken and written language, and to see how these processes change as children grow and learn. Using eye-tracking gives us a unique window into what changes are happening throughout these critical developmental years.

-Dr. Keith Apfelbaum